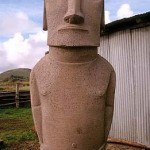

The Rapanui carver’s perspective: Notes and observations on the experimental replication of monolithic sculpture (moai)

This is an abbreviated version of a paper originally published in Pacific Art: Persistence, Change and Meaning (Herle et al. eds. Adelaide: Crawford House, 2002 for citations and notes).

Real Time and Individual Energy

Experimental archaeology is the systematic approach used to test, evaluate and explicate method, technique, assumption, hypothesis and theory at all levels of archaeological research. This paper employs a replicated moai to describe relationships between real time and individual energy, and explores the subjective artistic dimension of moai carving during an experiment lasting 32 8-hour days. It is drawn from journal notes taken by Van Tilburg from October 1997 to May 1998, by Arévalo from December 1988 to July 1999, and on written correspondence in English and Spanish between the authors.

Carvers and Craving

On Easter Island (Rapa Nui) ethnographic data related to monolithic stone carving methods, production techniques and carvers are scant. In the 1800s some Rapanui persons were distinguished by their relationships to ancestors who had been famed stone carvers. Katherine Routledge, co-leader of the Mana Expedition to Easter Island, 1913-1915, collected some names of statues that were said, in actuality, to be names of carvers, and believed them to have veracity.

In 1934-35 Anthropologist Alfred Métraux summarized the available traditions, including restatements from Juan Tepano Huki, an influential carver, of information he had previously provided Routledge. Tepano, in addition to being chief informant for both Routledge and Métraux, was C. Arévalo Pakarati’s great-grandfather. The exact source or sources of Tepano’s information regarding statue carving are not known, but he had direct access to what Routledge called the “living memory” of the small knot of informed elders still alive prior to 1920.

Tepano said that an expert in any craft was called maori. Carvers of the monolithic statues (moai) were known as tangata maori anga moai maea, and “they were a privileged class, highly esteemed, and their profession was transmitted from father to son.” Carvers worked under the leadership of skilled master craftsmen (tangata honui maori) and were presumably commissioned by chiefs or lineage heads. They were paid for the successful completion of their work in food, especially lobster, eels and large pelagic fish such as tuna (kahi) caught by expert fishermen called vaka tangata.

Previous Research

The first informed but unpublished calculations of time and manpower required to quarry and carve an Easter Island statue were made by William Scoresby Routledge, co-leader of the Mana Expedition to Easter Island, 1913-15. Routledge estimated that a master carver and a crew of 54 men could carve a “medium size image of 30′ long” in 15.5 days using basalt tools (toki). Thirty men first isolated a rectangular stone block, then undercut it to balance on a stone “keel.” Simultaneously, 24 men sculpted details of the statue’s upper surface, sides, top and base. The amount of stone to be hewn was, by Routledge’s careful calculation, 1690 cu ft, with each man able to remove 2 cu ft per diem. If the work force was reduced by 50%, Routledge reasonably stated that completion time would be one month.

Routledge’s characterization of a “medium size image” at 30′ (10 m) long needs some qualification. In fact, only two 10 m tall statues were ever successfully transported to their destinations on ceremonial platforms (ahu), and only one of them was successfully raised. Taller statues exist in the quarry and on transport roads, of course, but 10 m actually represents the outside limit of successful pre-industrial technology on Rapa Nui.

EISP mapping in Rano Raraku interior clearly shows that the “block system” of quarrying a sculpture “blank” that Routledge described was certainly used. Subsequent investigators have suggested that Routledge’s estimate was either too low or improbable. This research is not designed to test Routledge’s specific hypothesis, but does suggest that it is not unreasonable.

Replica Statue and Tools

A crew of Rapanui workmen under the direction of Ono Tuki used the mold created in our 1998 Transport Experiment for Nova to cast a concrete replica, after first placing within it a dated drawing and the names of everyone in the crew. The replica statue was removed intact from its mold on April 27, 1998. For the next three days, Arévalo Pakarati and Hito worked late into the night to shape the soft or “green” concrete with hand tools. During this stage of the work, ominous signs of bad luck related to breaking glass and the fiberglass mold were reported. On the same night the replica was removed from the mold Van Tilburg, distracted with many people and complex preparations, walked accidentally through a plate glass window and required emergency medical care. The consensus of many Rapanui people was that the moai was jealous and vindictive, and the accident was a wake-up call to Van Tilburg and the crew to pay closer attention to him or reap the whirlwind of bad mana. A traditional umu tahu (a ceremonial feast to assure success in work) was held to placate the moai and, in the interests of covering all bases, some in the Rapanui community invited the island priest to officiate during part of the ceremony. While the statue replica was created in concrete and not in Rano Raraku tuff, it was still “green” and could be detailed. It now became a valuable tool in our on-going attempt to understand the moai aesthetic. We decided to undertake finished carving of the replica statue using modern tools, and to document the process over the course of 32 days from December 1998 to July 1999. Our intent was not to replicate methods but, instead, to experience and understand subjectively the processes involved in carving a monolithic figure.

Our Roles

Throughout this work, Van Tilburg took on the role of commissioner of the statue. Initially, Hito and Arévalo Pakarati worked on the statue replica cooperatively and simultaneously in an attempt to move the work forward with some dispatch. It was soon obvious, however, that these two experienced carvers of more or less equal skill each had their own way of approaching tasks and their own personal vision of the sculpture. This contributed to slowing, not expediting, the work.

It was then decided that Arévalo Pakarati would act as master carver. When Hito later departed the island to return to his home in California Miguel Angel Arévalo Pakarati, who had no experience of carving, took on the role of assistant for 17 days, beginning on May 27, 1999. Miguel Angel was asked to act on all commands of the master carver “like a robot,” and did so with great willingness and remarkable attention to detail. Work was documented photographically and by daily written description of tasks, time, procedures, influences and interactions.

Journal Observations and Insights

Carving proceeded in 3 phases, no matter what portion or detail of the statue was being carved. Phase 1 was the “first cut,” taking off most of the blank material with the largest hand tools but always leaving a tolerance for later error. Phase 2 was the second cut, with a smaller hand tool, that removed an additional .5 to 1 inch of material. This was primarily to eliminate fractures, cracks and surface blemishes. Phase 3 was the last cut with the smallest hand tools sharpened to their greatest degree. In the words of the master carver, this was the cut in which he was “trying to find the body of the statue.” In was the cut in which the “art” lay.

From December 14 to 28 of the austral summer, Arévalo Pakarati worked alone as master carver for 10 days. He noted his progress every day in his journal, and quotes from that journal are presented in italics throughout.

Once in the heat, I was working alone and nonstop, climbing up and down when suddenly I lost my balance. I had been standing on the statue’s belly, and fell down to the ground. Question: is this the end of the first stage of carving or just the beginning of my collapse due to age? I suppose accidents in the quarry were a very important part of carving moai, especially when you hurry and are tired. But one of the most important things must have been keeping the prestige of the master carver!

Our replica statue was first carved lying supine, as were most of the statues in situ in Rano Raraku quarry. Evidence there is not conclusive, but facial features and torso details often appear at similar stages of development, suggesting that the timing for carving these features was related. In our experiment the master carver regarded the torso and head as discrete objects, and began shaping the surface at the torso. Part of his reason for making this choice was that the torso would be easier to carve than the head.

The statue head was slightly twisted to the right, caused by the photogrammetric data drawn from Statue 01 at Ahu Akivi. Prior to restoration, Statue 01 had been in two segments, head and torso. When it was re-erected, archaeologists placed the head on the upright torso with a crane and cemented it in place. Unfortunately the head was slightly askew, twisted to the right, and that was naturally reflected in our replica.

The master carver took the first 3 days to shape the base, the curve of the concave stomach and the line of the hands. The intended trapezoidal torso shape, which is one of the defining attributes of moai type and certainly one of its most beautiful characteristics, was cut from the original cylindrical, rectangular shape by giving special attention to the curve of the arms, the rounded shoulders and the shape of the base.

The result is greater harmony in overall symmetry, better attribute balance along vertical lines and a correct curvilinear shape to the arms. All of the cuts were made very tentatively due to the supine position of the statue, which made overall views of form difficult to achieve. Until the lines of the torso emerged, the master carver noted that the moai was “hiding, waiting to come out to the light.” It “seemed to be saying that we have never actually been carving him,” and have no “control over him.”

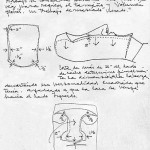

On December 21 the master carver turned to the head and face of the statue. The most crucial part of this work was to align the point of the nose over the navel and then with the hami (loincloth), creating a straight centerline between head and body. This centerline was essential, allowing the master carver to then proceed with all work on the head and face by referring only to the top of the nose.

Doing this, I “see” how important the alignment of the top of the nose, the navel and the hami is to this statue. It seems to me that these three points were connected by the artists…joined to suggest the taking in of air, the expression of sexuality and the creation of life.

Theoretically, at this point a second master carver could be added without the tension that we previously experienced when two discrete styles of working were involved. One might work now on the head and the other on the torso, with the nose efficiently serving as reference link between the two body parts. On December 23 the work focused entirely upon contouring the eyes and reducing the concrete surface of the face. Removing from 1.5 to 2” of material corrected its slight tilt to the right. At this point, the artist experienced a sense of control, of having the moai “belong” to him rather than to the person who commissioned it.

This was a wonderful day…to see the whole change from rectangular to trapezoidal gave me an incredible feeling. From my point of view, we both know that this statue is the culmination of all the things I learned from you, from all of the hours spent doing drawings, taking measurements and talking. But from now on the statue and his soul is mine, I don’t feel as if it belongs to you alone anymore. The change in him is magnificent. Even when I know that I must see him standing, I feel very happy to have him trapezoidal, his body on a correct line from top to base. He is now a real moai.

After a break for the Christmas holidays and the festivities of Tapati Rapa Nui, the master carver returned to Ahu Akivi to refresh his memory, take new measurements and formulate questions for discussion. He resumed work on December 28. The back of the statue posed a very big problem, since its slight curve is aesthetically important and significant to transport methods. No perfect example of the dorsal side of a statue this size was in our documentation and, in fact, probably no longer exists. A composite solution was reached using all 7 of the Ahu Akivi statues.

It was decided to take a break at this point. No more work could be done until the statue was erect, and that didn’t take place until May 24, 1999. The weather then was cooler and the heavy work of reducing the stone surface on the arms and back could begin. On May 28, Miguel Angel joined in to work on only on the dorsal side of the statue in accordance with our composite measurements. An inexperienced but enthusiastic assistant carver, he required control and strict supervision. To avoid mistakes, the master carver took the precaution of drawing his assignments directly on the statue’s surface.

The union of the head with the torso at the neck is the most complicated part of the carving process so far. The chin and the curve of the neck always seem to escape my control. Every single line in this zone is curved and maddening. At this point the level of material to be removed is so small that you can’t make any errors. My hand shakes. Nothing is done with a view toward time. A single small detail like the nostril really can give you big problems.

The perfectly symmetrical facial features, with special emphasis on the nose and eyes, occupied most of the carvers’ time on June 2, 4 and 7.

On June 9, an entire day was required to shape the top and back of the statue’s head. It was necessary to repeatedly withdraw from 5 to 15 meters from the statue to gain perspective, and then to climb on top of the erect statue’s head to do the actual carving. Some statues of average size held pukao, cylindrical headdresses carved of red scoria. We had made one to fit our replica and raised it in place on the statue by balancing it on the A-frame sledge used as a kind of lifting gantry. It was now clear to us, however, that making and moving the pukao was less difficult that was the precision carving required to balance it in place on the statue’s head. Coordinating all of this time consuming work was a most complicated feat

Carving the hands and hami in bas-relief took the better part of 2 days, and was extremely delicate work. The fingers are separated on the hands of some statues by double incised lines, an achievement the master carver found impressive and, in fact, daunting. Executing them required fine, sharp tools capable of precision work, a steady hand and very sharp eyes. In ancient times, it is probable that obsidian or sharks’ teeth were used to etch these and other, similar lines into the soft surface of Rano Raraku tuff.

On June 21, details of neck, ears and chin were refined, and insight was gained into possible organization of work tasks.

This day is wonderful because you can see the statue completely finished on its front, but I’m so tired that I don’t really feel too much accomplishment. The work done until now is so arduous that we are loosing the meaning of time, money and schedule. You feel like this and at the same time you know the ears are waiting for you! I think that we made a good observation when we looked at the real moai still on their “keels” in the quarry and realized that, at this moment, there must be a new kind of organization. Probably a great break for the carvers…new people and new skills had to be brought in and, I think, it is a good time for a feast.

June 22 was set aside to make “the perfect ears.” A pencil drawing was made on the stone to align the top of each ear with the respective side of the jaw, and the carving technique was a combination of incised and bas-relief.

As an artist, I find the ears of every moai are ugly things, out of proportion and badly designed. They make statues unbalanced. The designs seem ambiguous, too complicated and lacking perfection. Our statue’s left ear was always a little back from the front of the face because the head was twisted. Now balanced, I carved them so equally and level in size that you can’t see the difference.

The final two days of work were dedicated to finishing the details of the dorsal “belt.” An ensignia first documented in 1919 by Katherine Routledge of the Mana Expedition, it is found largely (but not completely) on statues associated with the highest-ranked or founding lineage. It was not present on the average sized statues of Ahu Akivi. On our statue, we chose to include it because of the carving challenge it offered. The design was first drawn by the master carver, roughed out in bas-relief by the assistant carver and then detailed by the master carver.

Because the details are so fine and delicate, above all where the belt looks like it goes under the hands to meet the hami, the work is incredibly difficult. I think carving it is the hardest part of the work with this statue…you can break the belt so easily….no wonder there aren’t many statues that have this design on their backs!

Significance to EISP

This work was enriched by our investigations in Rano Raraku quarry and it, in turn, opened our eyes to features there that reveal carving methods. Our map shows that there are clearly defined stages of carving. It also documents the carving canals (which are on slopes tilted from 26 to 32 degrees) surrounding the prone or lateral statues. All of them vary from 30 to 50 cm wide (with but few, eroded exceptions up to 70 cm). Some of them are stepped

This experiment, and our mapping in Rano Raraku, confirms our early observation that the crucial issue in carving moai is definitely not numbers of people. Clearly, once the “roughing out” accurately described by W.S. Routledge is finished a master carver and an assistant can advance the work far more efficiently working alone. This explains, in part, why so many carving canals in the interior quarries have so little room for large groups of workers.

Secondly, the mid-line of statue symmetry and balance can be established and used initially and most effectively when the moai is supine. During that time, two master carvers can coordinate independent work on head and torso. Once that is accomplished, however, it is then essential that one carver again resumes control. The alignment of the nose, navel and hami is crucial and the elongation of the nose is probably a deliberate reference for achieving mid-line balance.

The moai must be placed upright for at least half of the time required for finish carving. Details like the top of the head unexpectedly required a great deal of careful shaping, even if it was not intended that the head would ultimately support a pukao. Issues of perspective are constant throughout the work. Statues were raised to finish not only their backs but other details, and to provide perspective. Routledge’s unpublished excavation notes clearly show that some statues were raised on pavements, or were packed to remain upright in place, or were set up in carved basins. It is highly unlikely that such statues were to be removed.

“Green” concrete hardens over time, just as fresh Rano Raraku tuff becomes more friable after it is quarried and exposed to the elements. Timing is crucial in using both materials. A range of hand tool types from coarse to extremely fine was used, broken, blunted and then discarded, confirming observations made by many with regard to the plethora of discarded picks in the quarry.

The process of finishing this moai was not a constant, unbroken series of events. It was dependent upon the weather, community festivities, family obligations and available resources. Our statue was essentially complete on July 1, 1999, and is certainly the most accurate replica of the average moai yet made. Named “Moai Tangata Anga” (people working) by the women who participated in the transport experiment, will have a future in the community. It is a beautiful example of the carver’s art, a useful and instructive piece of work and a valuable teaching tool. Embedded within it, like the piece of paper with the names of all who constructed it, are extrapolated details, a bit of history, our own beliefs and identities and the stories of real people’s experiences.

Want to know more?

“The Rapa Nui Carver’s Perspective: Notes and Observations on the Experimental Replication of Monolithic Sculpture (Moai)”, by Jo Anne Van Tilburg with C. Arévalo Pakarati. In A. Herle et al. eds. Changing Themes in the Study of Pacific Art. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2002a.

English

English  Español

Español