Easter Island Statue Project History: 1985-1988

Goals and Methods

Stone surface conservation experiment conducted at Hanga Kio'E by Chilean museum authorities. ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo: J. Van Tilburg.

Data compilation and analysis, augmented by numerous field trips to the island and by museum study, were the primary goals of this period of research. The data were filed in what was, for the time, a rather sophisticated management program. The files have since been edited and transferred to other programs, however. All visual materials, including thousands of slides, black and white photographs, and negatives; hundreds of field sketches, notes, and maps were all organized within archival-safe storage. This effort, which was tedious at the time, was essential to proper use of the data, and laid the groundwork for the creation of the most comprehensive moai documentation archive in existence.

The specific task was to describe the moai as an archaeological artifact. Statue types were defined by shape of body and of head. A maximum-minimum size range for each type was defined and volume was calculated. Each type was a basic and discrete unit. Stylistic variations were outlined for such characteristics as hands, eyes, ears, and the dorsal design. The latter consisted of the hami(loincloth), maro (belt), and other related incised and bas-relief elements.

Specific research goals then could employ statue types to examine statue distribution and chronological relationships relative to the size and location of lineage centers, and to the presence or absence of pukao on ahu sites. Statue type, it was hypothesized, would relate to ahu construction type, and statue style sequence within the largest lineage centers would relate to ahu chronology.

At this time, the overwhelming weight of cumulative archaeological and linguistic evidence clearly supported an East Polynesian origin for Rapa Nui culture. This suggested that the sculptural emphasis that had been placed upon specific statue design components would be understandable within the ideological context of the Polynesian world view. Moai were presumed to be symbols of a dominant socio-political system defined as male, hierarchical, and lineage-based. Further, an understanding of the role of the statues as a legitimating symbol in the dominant ideology involved an appreciation of the existence of a subordinate ideology incorporating bird and other symbols.

In the Field

During the course of research and writing, two brief field trips to Rapa Nui were undertaken. With the help each time of Felipe Teao A., we re-examined and corrected field data at Puna Pau and at a number of coastal sites. Management of statue measurements was an on-going problem, and we needed to check discrepancies between those found on sketches, in field notes, and in other records. Statues in museum collections in Belgium, England, Chile, and the US were documented and added to the database. (See pages on Museum Objects Inventory.)

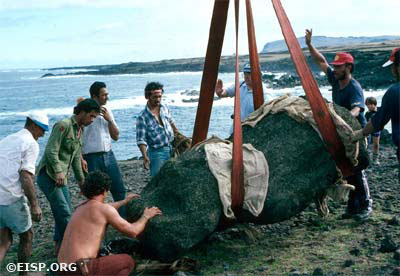

In 1986, Jo Anne Van Tilburg and Lilian Gonzalez N. observed a Rapanui team led by Juan Haoa retrieve moai head fragments and pukao from Hanga Te’e, near Ahu Vaihu. The fragments had been drawn and measured during EISP’s 1983 field season, and in Van Tilburg’s 1986 dissertation she urged their removal to dry ground. None of these fragments were documented by the Mana Expedition, but they had been in the bay since at least 1955 (when they were photographed by T. Heyerdahl’s team). Van Tilburg and Gonzalez N. were also present when Moai 007-585-001 (documented by EISP in 1983) was lifted from the seaside at Ahu Akahanga. It had been lying supine on the rocks below the small ahu on which it had once stood, and the two researchers took the opportunity to check the statue for a dorsal design. There was none.

The highlight of 1987 field work was the discovery of a moai torso re-carved as an impressive—and to date unique—bas-relief komari at Ahu O’Pepe. In addition, a comparative study was undertaken in the Republic of Belau. There we conducted an archaeological survey to document the stone statues found on the islands of Babeldaob and Koror, and did comparative ethnographic research in Truk and Ponape.

Pukao fragment ready to be lifted from the bay near Ahu Vaihu (06-255) ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo: J. Van Tilburg.

Rapa Nui crew, directed by Juan Haoa, removing pukao fragment from the bay near Ahu Vaihu (06-255). ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo:J. Van Tilburg.

Moai head fragment being removed from the bay near Ahu Vaihu (06-255) ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo:J. Van Tilburg.

Moai head fragment placed on high ground near Ahu Vaihu (06-255) after being removed from the bay. ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo:J. Van Tilburg.

Moai 07-585-001 lifted by a Rapa Nui crew directed by Luis Haoa from the rocks at the base of a seaside cliff. ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo: J. Van Tilburg.

Moai 07-585-001 placed supine on high ground near its original site (07-585). ©1986 EISP/JVT/ Photo: J. Van Tilburg.

Findings

In 1986 we had 130 statues sufficiently intact to allow for the creation of morphological types, and five emerged from our data analysis. They were ordered on the basis of numbers of statues included in each category. Statue Type 1 predominated, and was defined by a rectangular head and a rectangular body. Type 1A, which consisted on only one example, was the variant red scoria “pillar” statue (002-209-009) at Vinapu. Type 2 (16 examples) was formed of a vertically trapezoidal body and a vertically rectangular head. Type 3 (12 examples) possessed a vertically rectangular body and a horizontally rectangular head. Type 4 (9 examples) had a vertically rectangular body and a square head. Finally, Type 5 (8 examples) had an inverted trapezoidal body and a vertically rectangular head.

In 1994 we had 383 statues sufficiently intact to be entered in a computerized database. Of these, 134 had ten crucial measurements that defined body and head shape. Morphometric analysis defined size, shape, weight and proportionate relationships of head to body, producing a classification of statues. The first, preliminary classification arrived at in 1986 was revised. Essentially, there are four groups of statues. The first consists of statues that tend to be small and squat. The second and third groups are equally-proportioned but different in size. They range from medium-sized to large and have moderate proportions. Their body shapes are vertically rectangular and inverted trapezial. The fourth group is the large, vertically rectangular statues found standing on the slopes of Rano Raraku. They are distinguished by their slender proportions.

The numerically preferred form for ahu statues was the vertically rectangular, oval cylinder, while the majority of those still in Rano Raraku tend more toward rectangular slabs. Most of these slab-like forms are among the largest and latest in the quarry, and many stand erect on exterior slopes. It is this state that is most frequently photographed, and have come to be symbolic of Rapa Nui. The disproportionate size emphasis on the hands, head, eyes, and nose illustrates the iconic significance of these features.

Want to know more?

Hull, G. 1989. “Analysis of Easter Island Moai Typology in Terms of Socio-Political Units.” Paper in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Archaeology Certificate Program. Los Angeles: UCLA Extension Division and the UCLA Institute of Archaeology.

Van Tilburg, J.1986a. “Power and symbol: The stylistic analysis of Easter Island monolithic sculpture.” Ph.D. dissertation, UCLA Institute of Archaeology.

1987a. “Larger than life: The form and function of Easter Island monolithic sculpture.” Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire Bulletin, 58 (2), 111-30.

1987b. “Symbolic archaeology on Easter Island.” Archaeology, 40 (2), 26-33.

“Stylistic variation of dorsal design on Easter Island statues.” InClava ed. J.M. Ramírez, Viña del Mar, Museo Sociedad Fonck 4, 95-108.

“Anthropomorphic stone monoliths on the islands of Oreor and Babeldaob, Republic of Belau (Palau), Micronesia.” Honolulu: Bernice P. Bishop Museum Occasional Paper 31, 3-62.

“HMS Topaze on Easter Island: Hoa Hakanani`a and five other museum sculptures in archaeological context.” London: British Museum Press Occasional Paper 73.

English

English  Español

Español